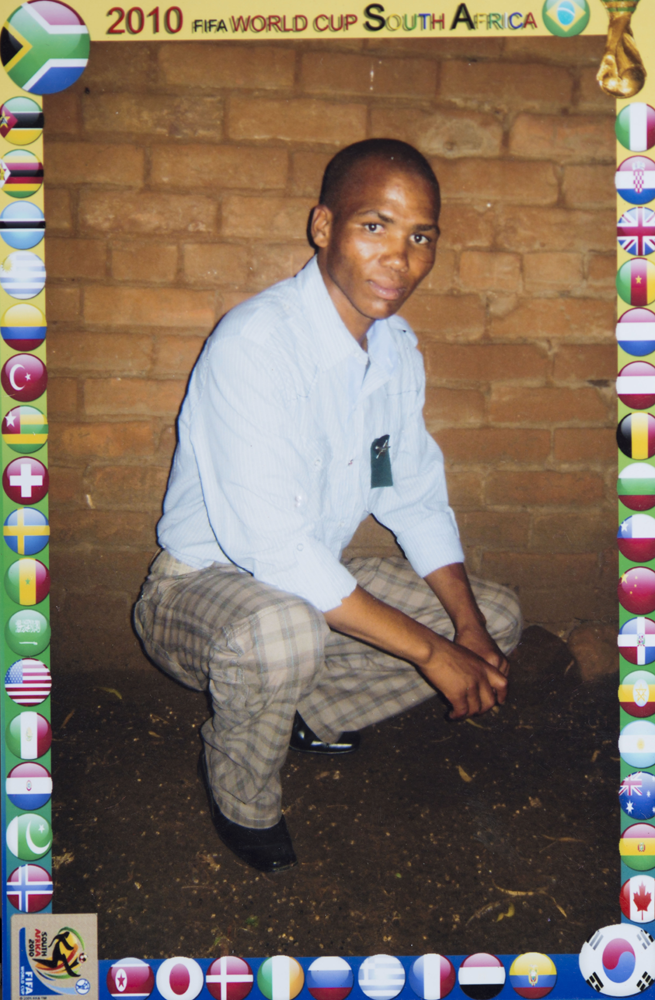

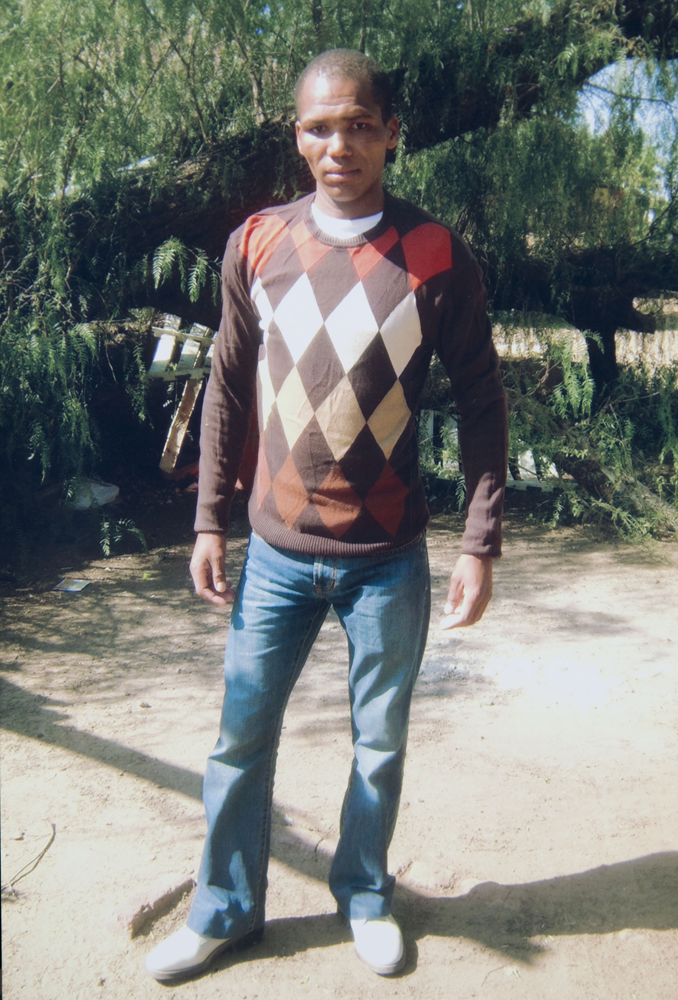

FEZILE SAPHENDU

KWAYIMANI, EASTERN CAPE

In the rural Eastern Cape, Saturdays are for attending funerals and Sundays for going to church and football matches.

With televisions and newspapers a scarcity, Ntombi Saphendu, the sister of miner Fezile David Saphendu, first heard about the massacre at a funeral on August 18.

“One of the speakers at the funeral said that 34 miners had died at Marikana and he asked us to pray for the families of those men. At the time when we prayed I didn’t know that my brother was one of them, but I had a strange feeling inside me,” she says.

With no airtime to call her brother and check up on his safety, she tried later from her other brother Thembinkosi’s phone: “Someone picked up the phone and then the call was dropped” and her suspicions grew.

Her mother, Nolindile, says she was at another funeral where she had a “very bad feeling that something terrible had happened”.

On Sunday, the elders gathered at the family home in Kwayimani, near Coffee Bay, to break the news of Fezile’s death.

The last time the family had heard from Fezile was the night before the massacre, when he had called to say he was returning home from church in Marikana. The 23-year-old miner was a devout member of the Zion Christian Church (ZCC) and his sister says he belonged to the choir, where he “loved to sing until the morning at the church”.

In his room in Kwayimani the framed pictures on the walls are of ZCC prophets and of the church’s holy ground at Mount Moria in Limpopo. Ntombi says her youngest brother was not political, but he was religious and had gone to the mountain on that fateful day “not to strike, but to get a report back from Lonmin and to deliver food” to some of his colleagues.

His mother says this was in keeping with his dutiful personality: he was always helping around the house, going to fetch water, walking with her to the local doctor to check up on her arthritis and doing considerate things like calling on Mother’s Day. He was also saving up to marry his childhood sweetheart.

“He was very young as a person, but he was mature,” says his mother. Sitting in her rondavel, her iqhiya (traditional Xhosa headwrap) framing a face lined like weathered sandstone that barely appears to register emotion, the 64-year-old Nolindile says: “What I miss most about my son is that he was a practical joker who always made his mother laugh.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.