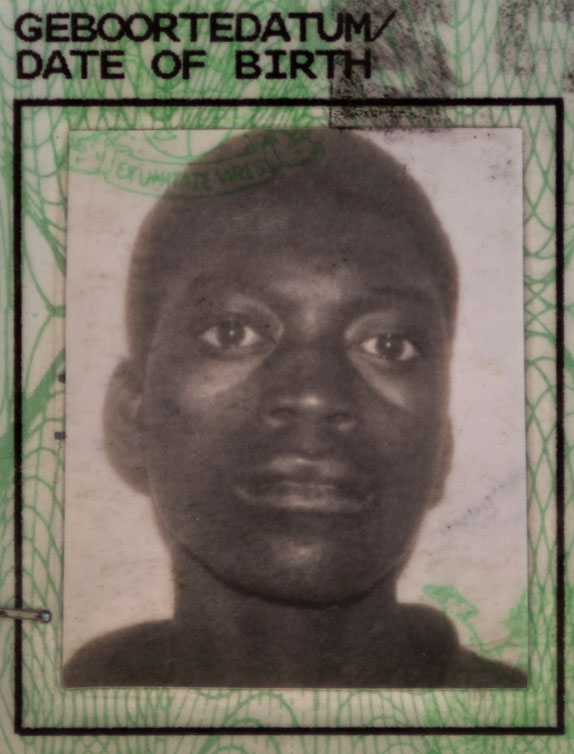

NKOSIYABO XALABILE

MTHATHA, EASTERN CAPE

Lilita Xalabile spent just 19 precious days together with Nkosiyabo Xalabile as his wife. They were married on July 7 2012. He returned to Lonmin’s Marikana mine after their honeymoon, and died in the massacre on August 16.

At our first meeting with Lilita, in March 2013, she was mourning alone in the room she was renting in Dalubuhle township on the outskirts of Mthatha. The little room felt like a solitary confinement cell; grief dripped oppressively off the four walls.

Lilita said that it had been difficult to grieve openly at her husband’s family home near Elliotdale in the Eastern Cape.

“My tears remind my mother-in-law and my husband’s family of their loss,” she said, fidgeting with her wedding band.

So, with her diploma in office management from the Walter Sisulu University, the 27-year-old returned to Mthatha to look for work.

She was intent on imagining and piecing together a life different from the one she dreamed of on her wedding day. It was difficult: jobs were scarce in Mthatha; pain and trauma were not.

“He was open,” said Lilita of her husband. “A quiet man, but he had lots of friends.”

She and Nkosiyabo were members of the Apostolic Faith Mission Church when they met at a church conference in 2011. He started calling her incessantly and she vacillated about whether or not to meet him.

“He would keep on calling me and calling me. Eventually we were going to meet on a Saturday, but then I changed my mind. I don’t know why. He buzzed me and I refused to meet,” she said.

Persistence appeared to make the heart grow fonder, though: “He kept calling me until my heart got absorbed by him.”

In the days leading up to August 16 Lilita had become increasingly anxious about her husband’s safety and had told him: “People say people are dying at Marikana, but I don’t even see it in the news. Why don’t you come back home?

“He said he didn’t have the money to come back and that management was going to give the miners an answer on Thursday. He said he had to go to the koppie every day because ‘it is better to die in the army than to get killed in the house’.”

In March Lilita was hanging on to her Christian faith for succour, attending church four times a week.

She later moved to Hermanus to live with her sister and continue her job hunt.

In a telephonic interview in August 2013, she says the move is helping her reconcile with her grief.

“I’m beginning to be free,” she says. “In Hermanus I can talk to anybody about whatever I want to talk about and it is healing me. In Mthatha people knew me, so even before I could open my mouth, they were feeling pity for me. I’m freer now,” she says.

Lilita is working as a cashier at a local supermarket and plans to continue her studies and complete a higher diploma in office management next year. Lonmin has agreed to pay for her education.

She is thoroughly disillusioned with the inconclusiveness of the Farlam Commission of Inquiry. “It is clear that the people [who did the] shooting at Marikana are known, but they remain unknown at the commission,” she says.

“The commission is exposing the families to all the footage of our loved ones dying, but, in exchange for opening all these wounds, there are no answers, no truth,” says Lilita. “Things are staying hidden at the commission, the truth is being hidden there. They should just close it down.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.