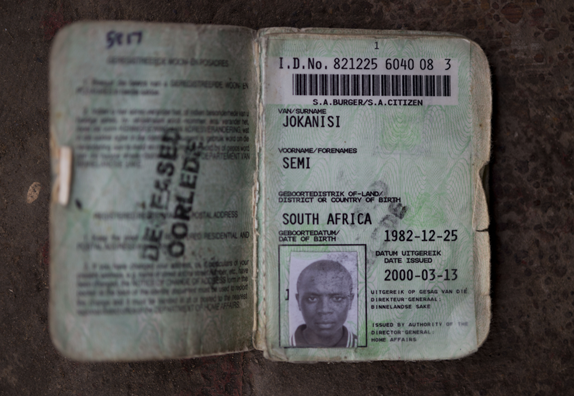

SEMI JOKANISI

LUSIKISIKI, EASTERN CAPE

Every day at Lonmin’s Karee Four belt shaft Goodman Jokanisi walks with the ghost of his son, Semi, who died in the days leading up to the massacre at Marikana on August 16 2012.

Father and son shared living quarters on the mine, but they worked different shifts. They would pass each other in the cages going up and down, or steal a few minutes together above ground if circumstances allowed. “Sometimes when I go to work I feel a spirit where I used to meet him,” says Goodman (57).

He is still haunted by anger, hurt and unanswered questions about how Semi died – the initial official version was that he was killed at the massacre, but it was later found that he had died three days before. “I’m still struggling at work asking questions that nobody can answer,” says Goodman. “But I feel, sometimes, that everybody must die.”

Goodman is a calm, soft-spoken man, but his anger at Lonmin is plain. “At some point at work I will say something that I don’t mean, like: ‘This company doesn’t like black people, all it does is drain our energy.’ I think later that that was uncalled for. But I am still angry.”

He adds: “After I buried Semi, I was not feeling well at all. I wanted to resign and go back home and suffer there. I didn’t want to suffer here.”

But the financial reality of having to support his five remaining children and Semi’s five children made retiring to mourn in Lusikisiki in the Eastern Cape impossible.

He is now the sole breadwinner for his large family, but is hoping that when the Farlam Commission finally completes its work, Lonmin will keep its promise to allow families to replace the deceased miners, so that his son Anele may join him.

Goodman has taken over the responsibilities of his son, who was a winch-operator, which includes completing a house he was building in Lusikisiki in anticipation of his marriage in December last year.

“I will not let him down,” he says. “This house he was building was beautiful. Semi liked beautiful things … He wanted expensive things, but I can’t afford all of that. I will put a cheaper gate because I can’t afford the one that he wanted. But I will complete it.”

In Lusikisiki, his wife Joyce mourns both for the loss of her son, and what it has meant for the running of her household.

“I cry sometimes because the children carry bread to school with just Rama [margarine], not even with jam,” she says.

Goodman has been a miner since 1980 and says the migrant nature of the work “is like living in a waiting area because your home and family are back there [in the Eastern Cape]” and that while conditions have improved because of trade unionism and there is less tribalism, “the employers still only care about production”.

Goodman was on leave at home when the strike began and in their last telephone conversation he had warned Semi that strikes are dangerous.

“I told him I know it’s hard not to be involved in the strike, but when he is there he must not go to the front, and he should remain neutral”.

Semi had gathered some friends to help his father pack all the items he was taking back for the household in Lusikisiki as he prepared to go on leave, and Goodman bought them some beers in appreciation.

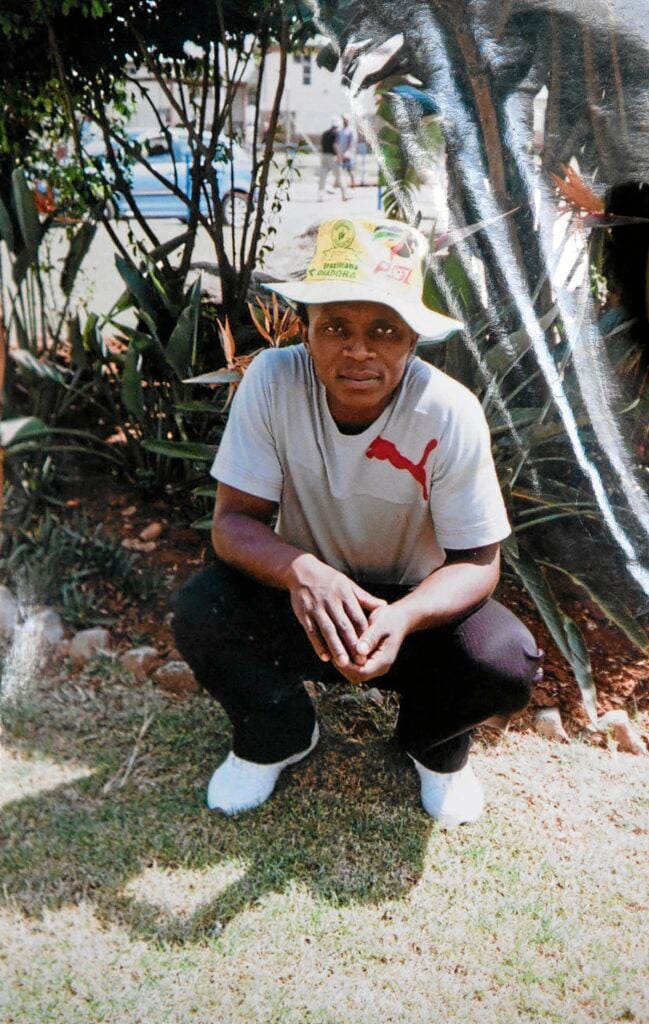

“We sang traditional songs on the way to the bus home,” he says. “Semi was a good boy.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.