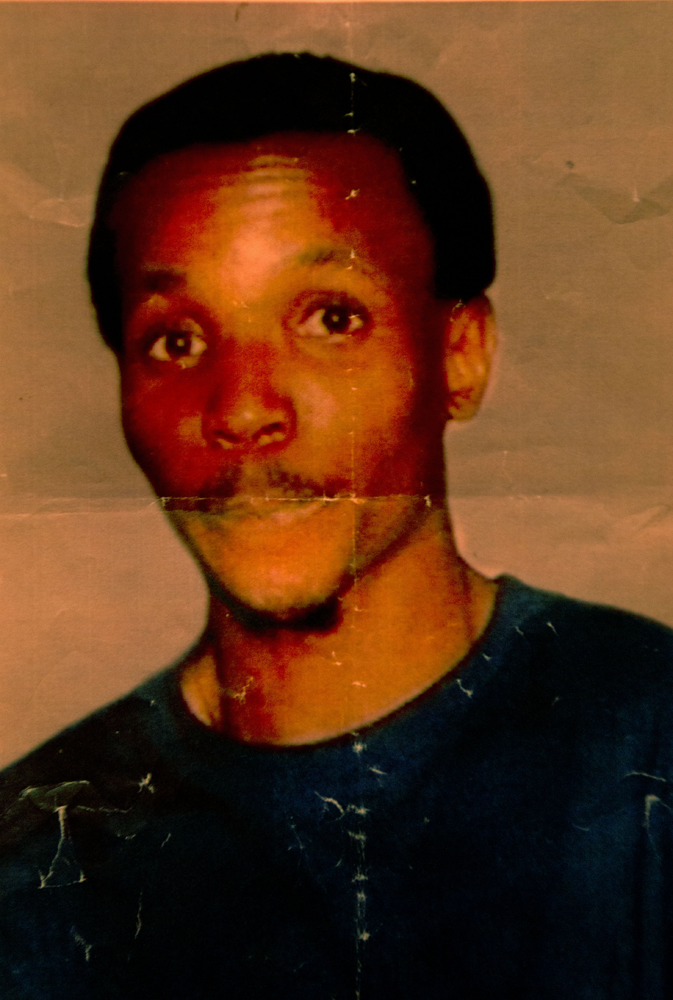

MVUYISI PATO

NEAR BIZANA, EASTERN CAPE

The bodies of the dead miners at Marikana did not lie on the ground long enough to attract carrion-feeders, but vultures have been circling their families ever since August 16 2012.

“People started calling us soon afterwards saying they wanted to be our lawyers and that carried on into this year,” says Mongezi Pato, whose son Mvuyisi was killed at the koppies. “But I tell them that we are represented by lawyers already.”

His wife, Alexia, adds: “In October or November, someone offered me R500 to sign some documents and they said that they will help us get money for our son’s death. I refused.”

This sort of opportunism runs through the post-Marikana experience for many families. Sometimes they feel it from the government, too.

Sixty-five-year-old Mongezi is a can-do sort of guy. When he heard of Mvuyisi’s death he went to Marikana to identify the body and found it “doubly heartbreaking” when he saw how his son had died. “It looked like he was shot in the back. It showed that he wasn’t fighting.”

Mongezi “decided to never set foot in Marikana again” and brought Mvuyisi home as quickly as possible for the family to bury him and then try to move on with their lives.

At the time, unaware that the government had committed R25 000 for each family’s funeral costs, Mongezi paid for the funeral by selling one of his cows. He is still owed R8 000 by the Alfred Nzo municipality in Bizana, near where he lives, and is struggling to get that money reimbursed.

The food parcels that the municipality delivered for Mvuyisi’s funeral also showed signs of pilfering: a case of 340ml milk containers had been opened with only five remaining. And some of the items included, like two tins of fish and five kilograms of mealie meal, were derisory in the context of huge communal funerals where a village has to be fed.

Alexia says this was an affront to her family and her dead son.

Mongezi says his son was due back home in August to begin lobolo negotiations to marry Nobungcwele, the mother of his two children, Cebo (4) and Sinawo (2).

“My son was saving up to get the cows necessary for the lobolo. Now there is a vacuum where he would have been, and the many grandchildren he would have blessed me with,” says Mongezi.

He has completed the house nearby that Mvuyisi had started in preparation for married life. “My dream is to fill the house with my children and the children of my deceased son,” says Mongezi. “I had to complete it. I see my son in this house.”

He says he has used the R15 000 he has so far been reimbursed by the government for the funeral to complete the house.

During a tour of the house, Mongezi remarks on his son’s green fingers, and his love of gardening.Pointing to an orange tree in the yard where he had recently been adding fertiliser, Mongezi says: “That tree is a symbol of a person who had care and love. When I see the tree bearing fruit, it also reminds me of my son.”

The couple appears to find joy in the little things that remind them of a son who his mother “a joker, a comedian who always made people laugh”.They find it in the trees that he grew, and in the horses he trained. They reconnect with Mongezi through his two young children whom they evidently adore and who are constantly running around under their feet.They find joy in the gargantuan things, too. Outside the family home a pig that rivals President Jacob Zuma’s nephew, Khulubuse, in girth is snuffling around for more food. Mvuyisi brought the pig home before he died and he has become a family pet.”We treat him as if he is family too,” says Alexia with a laugh. “He eats a lot, but he brings us happiness.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.