He dreamed of flying

DIPUTANENG, LESOTHO

The dead fly to Diputaneng. Or sometimes they ride, strapped across horses. For the living, it’s a three-hour drive out of Maseru and past Semonkong on increasingly steep and treacherous roads before parking at the scattered hamlet’s local school and completing the last two and a half hours on foot or horseback.

The footpaths wind along the mountains’ ravines as the oxygen thins to a breathtaking nothing with every step higher into the remoteness.

Molefi Ntsoele’s coffin was flown to his homestead in the area in September 2012 – weeks after the miner had been shot and killed at Marikana.

Ntsoele’s final journey is tragically ironic for, as his wife Matsepang says, “he’d worked hard and always dreamt of flying somewhere to go on a holiday… but that never happened.

“He used to break down to me and say that mining work is slavery, that his superiors never bothered to care about the miners, but he worked to make an example to his children… He worked to better their lives.”

The Ntsoeles have four children, aged between five and 19 years old.

Matsepang says her husband would send home R3 000 every month to help the family survive, but had also invested some money for their future. The couple appeared determined to use the money Molefi earned in the mines to improve their lot. There is a house built in Maseru for the family but with extra rooms that are rented out for additional income, and a stall purchased in the Semonkong location intended to be developed for the same purpose.

Matsepang says that because of her husband’s death, construction on the Semonkong plot has not started. A two-room extension planned for the Maseru house has also stalled.

“The dreams I had with Tata Molefi I hope to continue, though, with the money that Lonmin will pay me,” she says, of the two-tranche provident fund payment from her husband’s employers.

Widows will receive the second half after the anniversary of the Marikana massacre.

Matsepang says her husband was “experienced in financial matters”, keen on business ventures and always searching out new ways to earn more money. This is evident when she riffles through his papers looking for a provident fund document: in the file is a catalogue from a cosmetic sales company’s pyramid scheme. Molefi’s provident fund payout was also among the largest of all the miners who died at Marikana.

Like many miners, Molefi Ntsoele had also been investing in livestock since he went away to the mines in 1996. Matsepang can count more than 60 sheep, three horses, seven donkeys, 20 goats and 22 cows milling around in the kraals outside her rondavel in the mountains.

Remarking on her livestock, she says: “There is a saying that your heart is otherwise if your animals don’t multiply.”

Her own heart was captured by Molefi while they were in high school, she says. “He lived in nearby Halabane and I just fell in love with him.”

Matsepang’s mother died in March and on the night of her cleansing ceremony on May 5, one of her shepherds, Tsidiso Metsing, and Molefi’s aunt, Mmamokoena Mokitimi, gather in her rondavel warming themselves against the sort of cold that makes even ink in a pen harden.

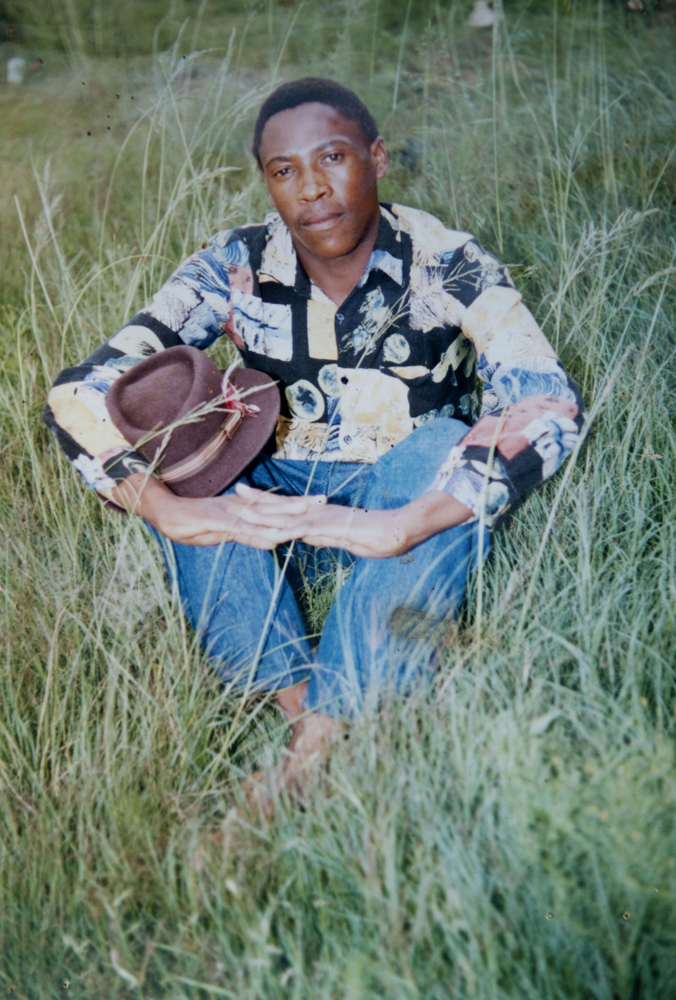

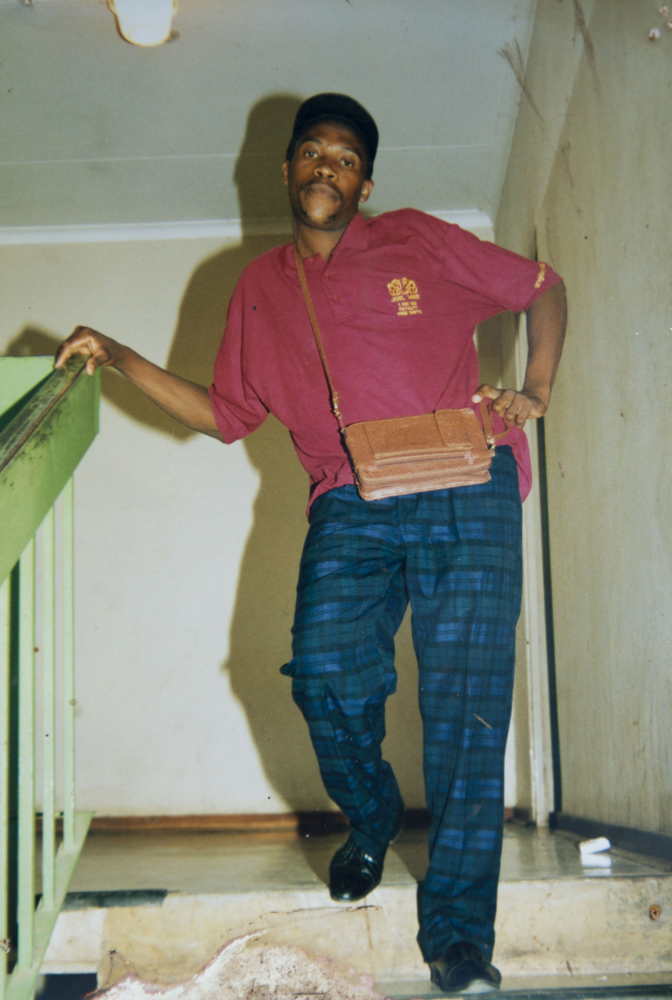

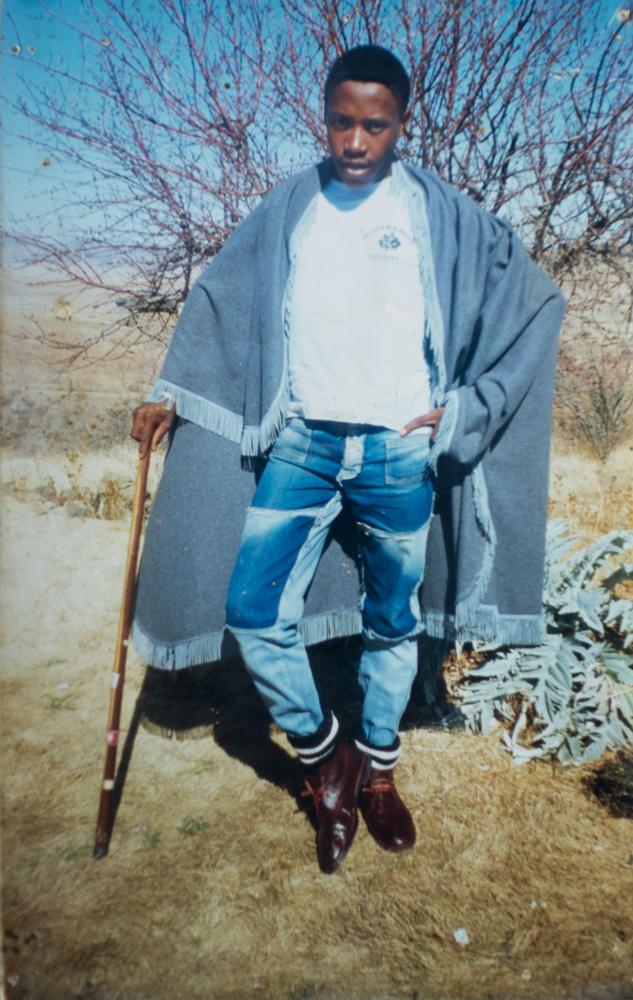

In the light of a paraffin lamp, Matsepang produces family pictures, including one of her as a teenager in her high school uniform, and a picture of Molefi as an 18-year-old. There is another of Molefi in his mining overalls, his helmet tipped rakishly to the left. “We had a child out of wedlock when I was 17 years old, he was 19. We were already living together at the time, but this year we would have been married for 20 years,” she says. Mokitimi chips in, laughing: “They were hungry to get married. He was naughty, very naughty.”

When photographer Paul Botes produces pictures taken at Molefi’s funeral, including one of Matsepang with her sister and Molefi’s sister, we can hear the lump in her throat. She doesn’t remember the picture being taken, or even the presence of the photographer – who, as one of only two white men present, would have been hard to miss.

Matsepang apologises for not remembering the photographer. The next day, describing her response to the news that her husband had been killed in Marikana, Matsepang says: “I was in a twisted mind, asking: ‘Who is this Molefi that you tell me is dead?’ That is why I don’t remember people who came to the funeral. I can’t remember the funeral.”

It had been snowing in the mountains in August last year and Matsepang had been snowed in at her village. She had spoken to Molefi the Sunday before the massacre, but further attempts to contact him during that week had been fruitless. She had put it down to bad reception because of the weather and only found out about his death when she received a telephone call the following Sunday.

In the early morning, when the sun is just nibbling at the Thaba Putsoa mountain across the valley from Matsepang’s home, the Breipal river that separates the two outcrops flows as if it were cut glass.

The shepherds, returned from the drinking session that followed the cleansing ceremony at Matsepang’s father’s home last night, are nursing slight hangovers as they release sheep from their kraal and gingerly feed the horses stalks of maize.

The only sign of the wider world are the vapour trails streaking the sky, left by planes that occasionally fly overhead. Marikana and the Farlam Commission of Inquiry, set up to find out what really happened, appear to have been frozen out of this world, so close to heaven. Those are part of another world.

A world Matsepang is not eager to return to.

She finds the commission useful “for information about my husband” but does not trust what is happening there. “I don’t have faith in the truth being uncovered because of the testimony of the police and the National Union of Mineworkers – they are not respectful.”

Matsepang says the commission is also dragging on too long, and every day she spends there is a day better spent ensuring her family’s financial future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.