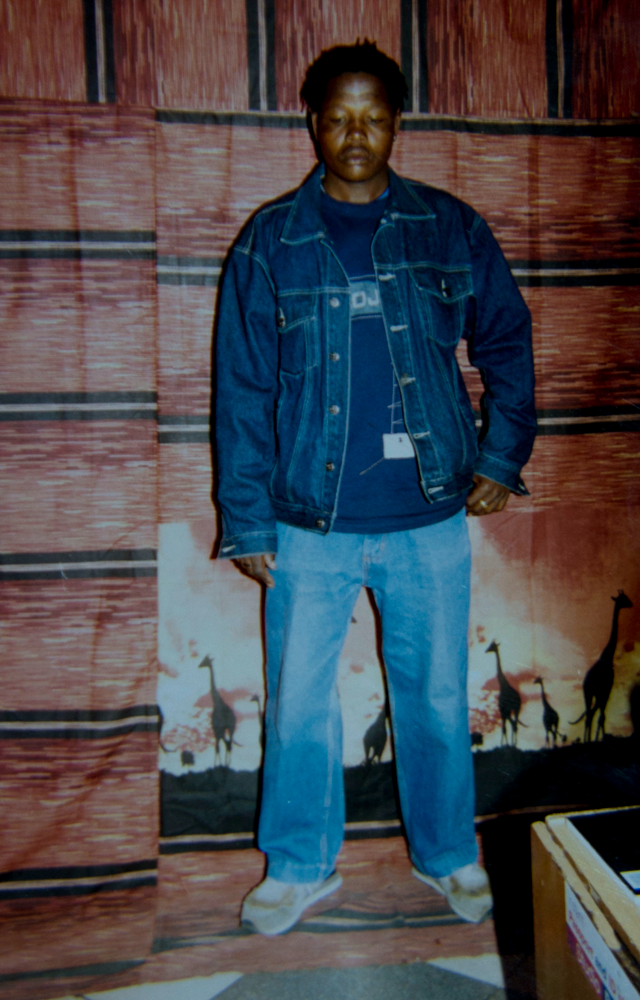

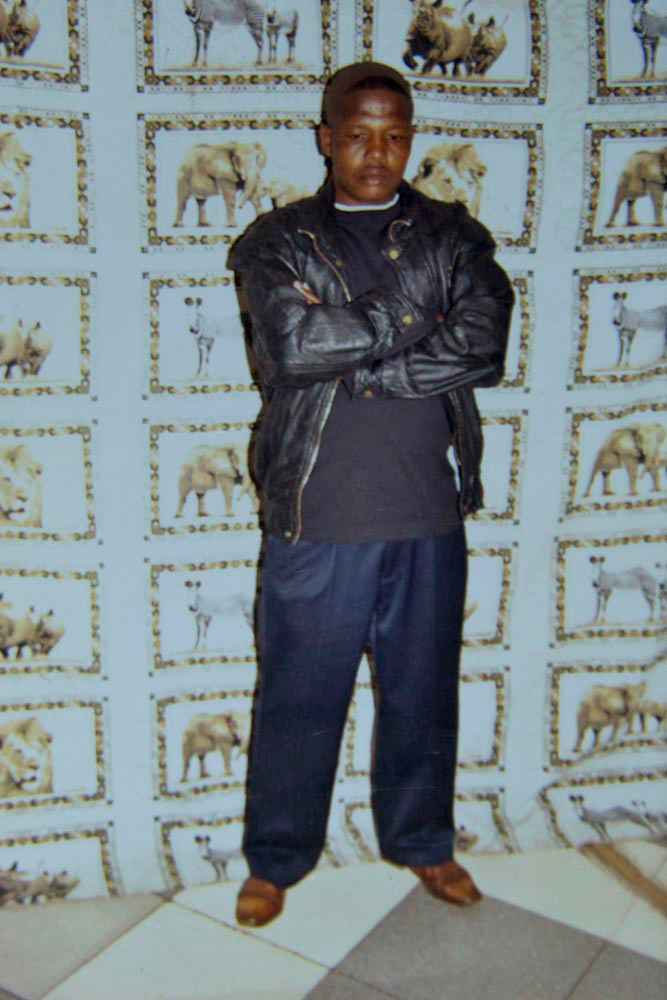

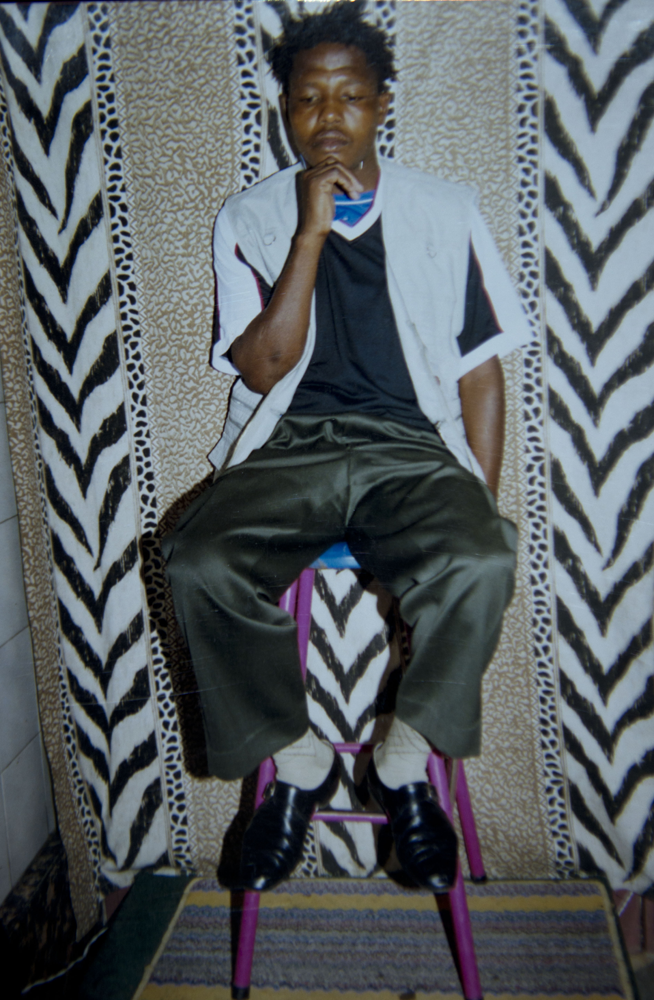

THOBISILE ZIMBAMBELENEAR LUSIKISIKI, EASTERN CAPE

THOBISILE ZIMBAMBELE

NEAR LUSIKISIKI, EASTERN CAPE

The photograph of her husband that Nokuthula Zimbambele keeps on her phone is no ordinary snapshot – it is a grim memento of violence and loss. “Here is my husband,” she says, offering the picture after gathering herself from tears. Scant warning, even in this age of countless everyday clicks.

It is a press picture taken off the internet. In it, a policeman is lifting Thobisile Zimbambele’s body off the dust and blood at Marikana’s koppies after the massacre there on August 16 2012. Thobisile is being held by the arm by a policeman and hangs limply to about the waist. He is surrounded by corpses, and by R5 – wielding amaBerets (the tactical response team).

“I think they were finalising that he was dead,” says Nokuthula. “But I think he might have been alive there.”

Since Marikana, Nokuthula has lost all trust in the police and says her whole body shakes when she sees a policeman.

“They have no mercy,” she says. “How can you shoot and kill someone and then kick a dead body? I shiver when I see the police.”

Nor has she been impressed with police testimony at the Farlam Commission of Inquiry, which, she believes, is bent on “hiding the truth”.

“You can see during crossexamination [of police witnesses] that just as the truth is coming out they don’t answer the questions directly,” she says.

Disbelieving of police commissioner Riah Piyegah’s claim to the commission that police were defending themselves, Nokuthula says: “There are things that make a woman: Sympathy and mercy. She has none of that.”

The photograph is not the only thing Nokuthula carries with her. It is on her shoulders that the burden of clothing, feeding and sheltering an entire household falls. “We dish 11 plates in this house,” she says.

There are her six children plus an orphaned niece, her Mamazalo, or motherinlaw, and the latter’s two children. Nokuthula must also surely eat, but there is little evidence of that on her thin body.

Mamazalo, Thobisile’s biological mother, deserted her son and his three sisters when they were young, says Nokuthula. He was raised by his grandmother, Thandiwe Baca, who died in March 2012.

According to Nokuthula, Thobisile longed for the mother he never knew and spoke of her often “But he thought she was dead,” she says.

When Mamazalo returned to the family home just outside Lusikisiki in the Eastern Cape in February 2011 Thobisile was at Lonmin, but he quickly came back.

“He couldn’t wait,” says Nokuthula. “He came back and hugged her and said: ‘Mama, you can’t leave again.’… He said, ‘I wish I will have a long life to recover the time I lost with you, Mama.’”

Thobisile’s father had remarried and Mamazalo had no home to live in. She asked her son to build a house for her and his four halfsiblings.

“He said he would build a house,” says Nokuthula. “He died before he could fulfil that promise, but I have continued that work.”

So far she has spent R35 000 from policies paid out after Thobisile’s death to build a rondavel and a tworoom flattopped house for her motherinlaw. All that remains is for the walls of the “flat” to be plastered and Mamazalo will be able to move in.

“My husband was loving and caring and his dream was to build a house for his mother,” she says. “I made sure I fulfilled that dream because of my love for my husband. I ensured that it was completed so that he can rest in peace.”

But in doing so, Nokuthula has compromised her own immediate future. She knows this only too well, and rarely rests easy. With the children’s education paid for by Lonmin, the financial burden has eased, but with only child support grants to rely on, “money is either for clothes or for food, not both”.

“It’s a hard, very difficult life,” she says.

Like many widows, she is no longer able to scrape together enough money to participate in the monthly stokvel, which always brought in handy additional funds.

Her husband had four children out of wedlock and sometimes they visit, for as long as a month, inflating the roll call at the family’s single daily meal. Her biggest challenge, says Nokuthula, “is food in the stomach … ensuring that 10 stomachs are filled at sunset”.

“Sometimes the children ask, ‘Mama, when are we going to eat eggs again? Why is it always cabbage and potatoes?’ I can only answer that they must get used to it,” she says.

Nokuthula is determined, but sensitive and gentle. This is evident when her dogs run up to meet her at her gate and jump to lick at her hands – unusual in the rural Eastern Cape where canines are often treated like Dickensian orphans and cower from their owners.

She says she wants “to concentrate on my garden again, so that the money I spend on vegetables can be used for something else”. But it has been difficult, because attending the longrunning Farlam Commission hearings has left very little time for gardening.

And what small crops she has managed to grow are being raided by the animals that have taken to slipping in through the fence, which has grown porous of late.

“When I am at the commission and the firewood runs out, the children [who are left in the care of her oldest daughter, 21yearold Sandisa] don’t bother to go to the forest and collect more,” says Nokuthula. “They just take it from my garden fence.”

The commission is of little help, she adds, because “there are only moments of truth”. It is clear, too, that as the commission drags on, so too do the material and familial repercussions pile up for those whose loved ones died at Marikana.

Yet Nokuthula has none of the fatalism she sensed in her last conversation with her husband on the morning of August 16.

Over the phone he had told her that Lonmin was going to respond to their grievances that day.

“And he said, ‘But if I die, don’t cry.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you return?’ And he said, ‘No, no, no. Don’t call me again … If I am left behind on the koppie, you will hear from the others.’”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.