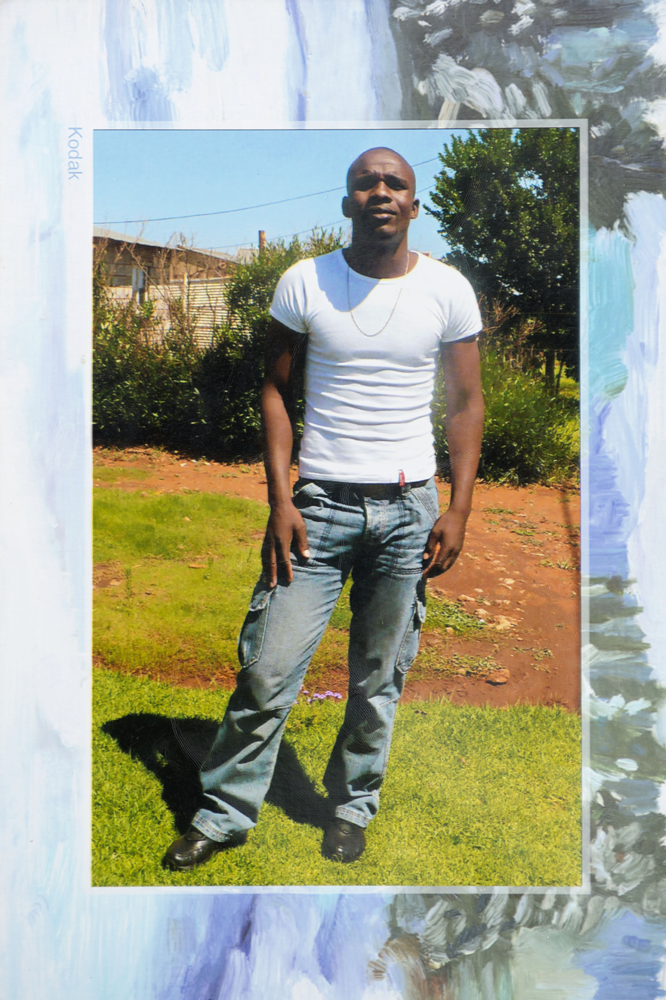

MGCINENI NOKITHWALIKHULU, EASTERN CAPE

‘The man in the green blanket’ is unfamiliar to the family of Mgcineni “Mambush” Noki, who was killed at Marikana during the strike for which he had become a media poster boy.

Mambush’s younger brother, Sinovuyo, says: “From what we saw [on the television and in the newspaper photographs] he seemed to be acting aggressively, but that was very uncharacteristic of him. I didn’t recognise him.”

Another brother, Mbulelo, who works in Carletonville, had visited Mambush at Marikana during the strike and Sinovuyo remembers that in a telephone conversation, “Mbulelo said Mambush had become a strange person and that he was acting very aggressively. It was not the brother we knew from childhood.”

Sinovuyo says Mambush was an easygoing man, who, when he was younger, or on holiday from the mines, spent his time at Thwalikhulu in the Eastern Cape leading a quietly pastoral life.

“Mambush used to tend his cows and goats the most,” he says. “That is what he loved doing.” His brother also loved football and played in central defence for the village team, where “he was a leader and an organiser” and excelled to the point of being voted the best player in the Mqanduli District.

Describing Mambush as a “nice person”, Sinovuyo relates the story of how his grandmother was accused of witchcraft and murdered by a mob wielding axes in 1996. He said the man who had made the allegations had borne animosity towards his grandmother.

“Mambush knew the man who killed our grandmother, but he didn’t hold a grudge against him — he was forgiving. My brother used to greet him and ask: ‘How are you doing?’”Ruminating on the death of his grandmother and the — as yet unproven — allegations emanating from government that the striking miners had thought themselves invincible because of the use of muti, Sinovuyo says: “Maybe there is an evil spirit around the family which is making people die … Maybe it’s just bad luck.”

The portrayal of Mambush during the strike still affects the family. His wife, Noluvuyo, remains hesitant to speak and Sinovuyo says his brother’s name has been “blacklisted” by some in the community. “Sometimes you feel scared and you feel like you don’t want to go out and see people,” he says.

Together with Mbulelo, Mambush — who had several children of his own — supported his four younger brothers and sisters after their parents died in the 1990s.

Sinovuyo says Mambush was planning to build a bigger home for the family and was also hoping to “surprise us by buying a car”. He hopes to replace Mambush at Marikana but, so far, there has been no offer from Lonmin.

Asked whether he is wary of working on the mines in light of the way his brother died, Sinovuyo says: “No. If I get a job on the mine it will make me feel like I am growing up because I will be supporting my family. I will be a man … I want to complete my brother’s dream of building a new house.”Sinovuyo says he was unable to move on after Marikana until he attended the Farlam Commission of Inquiry: “The only way I could see the future was by confirming to myself that my brother was dead and finding out exactly had happened to him.”

“The police were so dangerous to my brother,” Sinovuyo says, remembering the day he saw the footage of his brother being killed. “I didn’t call the family to update them that day – I was too angry. It was unbelievable to see someone speaking, speaking, speaking and then pointing the bullet at him.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.