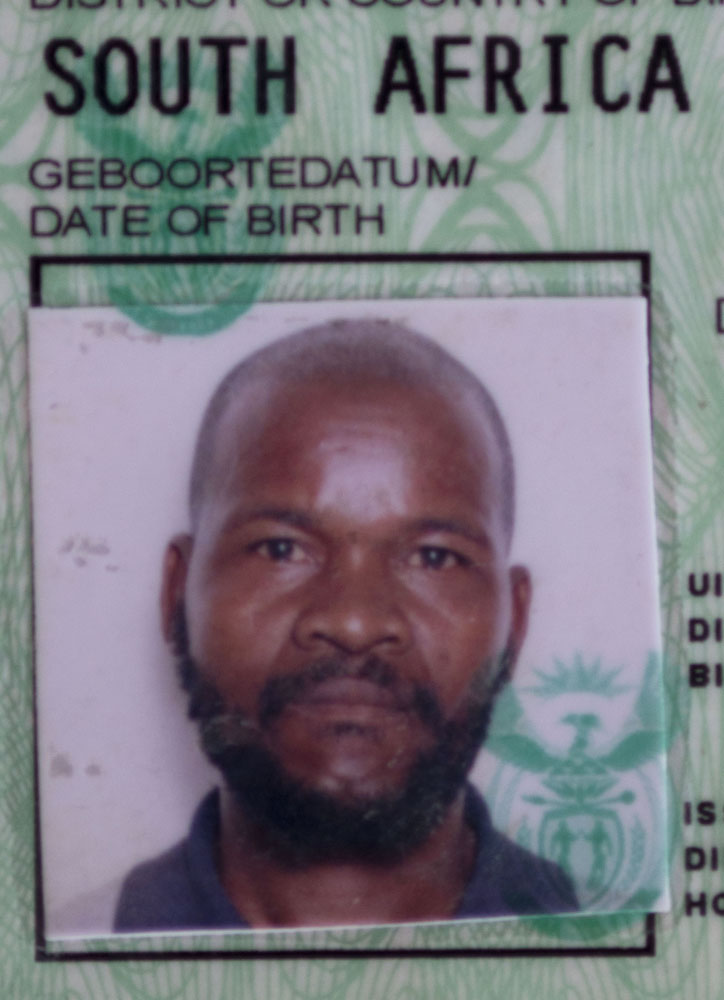

MPHANGELI THUKUZA

NGQELENI, EASTERN CAPE

Nokwandisa Thukuza broke down and sobbed as she recalled being summoned to the gathering of elders that her father-in-law, Tshoshotsho Thukuza, had convened to inform her and the rest of the family that his son, Mphangeli, had been one of the 34 miners killed by police on August 16 2012.

Tshoshotsho intervened. “I can’t allow this to continue because you are taking us back and we are trying to move forward,” he said. “I’ve moved forward, and I don’t want to move backwards. I told you I want nothing to do with Marikana.”

Tshoshotsho is a sternly traditional Xhosa man, a self-styled “Abraham from the Bible”, whose virility he attributes to “having God in me”. His family once numbered 13 children, 29 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren. Since Mphangeli’s death, he has only three sons remaining.

Like any patriarch, Tshoshotsho’s word is the law in his house. The interview ended.

Mphangeli’s second wife, Nolundi (35), moved silently to complete household chores, following instructions from her mother-in-law.

Nokwandisa (39), who had returned home from work in Northam that morning, went to play with her junior wife’s children, especially the four-month-old baby born in January this year, about five months after Mphangeli’s death.

That the family rarely spoke about Marikana or their loss — as per decree — was clear.

Earlier that day on May 9, Nolundi had told representatives from the National Development Agency (NDA) and the department of social development that she had been refused a birth certificate for the baby by nurses at the nearby Old Bunting government clinic.

“They said they were punishing me for giving birth at home,” she said.

The three women from the NDA and the government were visiting to assess whether the Thukuzas’ land and resources could sustain a food garden programme.

The project would “provide training to plant and grow spinach and cabbage”, which, according to the department’s Nokonwaba Mxego, the South African Social Security Agency would then purchase from the family. Tractor rental, seeds and water would be provided by the development agency.

It was a project that Tshoshotsho said he would consider, together with his eldest son, Mketheni, but he remained noncommittal.

Months later, in “New Stands” location in Northam, where Nokwandisa rents a room extended out of an RDP house, she is eager to have a picture taken with her hatchback car.

Away from the rural Eastern Cape, it is a sign of her financial independence — which she revels in, as earning money means more freedoms, she says.

Nokwandisa has been working underground as a bell operator at the Tumelo platinum mine for the past two years. She had been estranged from Mphangeli for a few years and in that time had found a job and had another child, Phumeza, who was born in 2008.

The couple had been attempting to reconcile when her husband died. Mphangeli had called just before six on the morning of August 16.

“He asked again how Phumeza was doing and said he wanted to spend more time with the child because he was unfamiliar with her,” says Nokwandisa.

Even though Phumeza was not Mphangeli’s biological child, she will be considered as such according to Xhosa tradition, says Nokwandisa, so her husband was “making an effort” to know her.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.