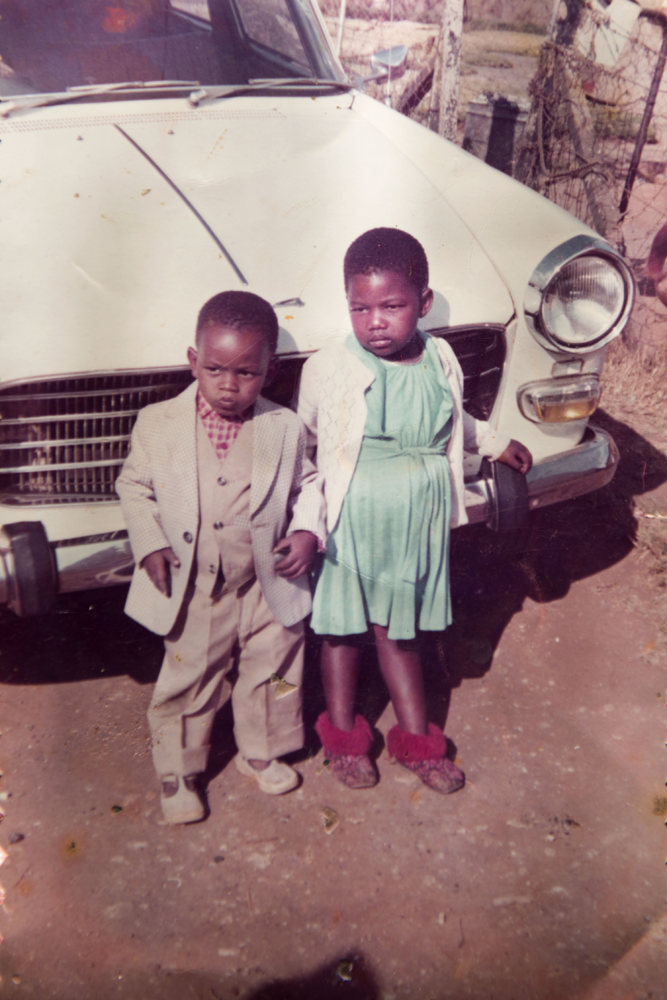

BONGINKOSI YONA

KWAMAQASHU, EASTERN CAPE

Bonginkosi Yona was nuts for Kaizer Chiefs. He would sit entranced, giving a running commentary while watching their games at home on television. This passion eventually converted his wife, Nandipha, to the yellow and black.

Remembering the Amakhosi match they attended together at the Royal Bafokeng stadium in Rustenburg while she was heavily pregnant, Nandipha laughs: “Chiefs were losing but were attacking and trying to score. He joked that I shouldn’t go into labour at the stadium because I would have to go and give birth on my own.”

Their baby boy, Mihle, was born on August 7, nine days before police at the Marikana koppies killed Bonginkosi.

Sitting in her tworoom house in KwaMaqashu in the Eastern Cape, with a picture of the couple kitted out in Chiefs clobber hanging on a wall, Nandipha says her husband was excited about the birth of their second child – they also have a sixyearold boy, Babalo – and when scans could not ascertain Mihle’s gender, Bonginkosi remained adamant that he “will only have boys”.

“I wanted a girl and I hadn’t bought any clothes because we were not sure,” she says.

When Nandipha was discharged from hospital, Bonginkosi, who was earning R5 000 a month, told her that a strike had started at the Lonmin mines over better wages. Fearing for his safety, she had warned him to stay at home, but he said the strike was important “because we have another mouth to feed”.

Returning to their shack in Nkaneng with her newborn, Nandipha remained anxious about her husband’s safety, remembering when he had been shot during a strike at Groblersdal, where he had worked before moving to Lonmin in 2010: “He was going to work when he was confronted by some people. A fight started and he was shot in the leg. He came home, showed me the wound, cleaned and bandaged it and then went back to work. I was fearful that something like this would happen again,” she says.

Her anxiety meant the couple never discussed the strike and she was “relieved every day when my husband would return home from the mountain for lunch, and then in the evening”.

But on August 16 Bonginkosi didn’t return for lunch. Or supper. A neighbour told her about the shootings, saying that “people had been killed, injured and arrested and my husband could be any of these”. He then went out to look for Bonginkosi – in vain.

“The following morning I went to the Bethal Prison and my husband’s name was on a list of people arrested. I asked the police to call him. They said they did several times, but he wasn’t there and I should go away. They swore at me, but I refused to go because his name was on the list. Eventually I went to every single cell in the prison calling out his name, but he wasn’t there,” says Nandipha.

Bonginkosi’s younger brother eventually found her husband’s corpse at Phokeng mortuary on the Sunday. Reliving the moment she was told of her husband’s death, Nandipha says: “I see myself sitting on the floor, but I don’t remember anything else.”

“Even though he held Mihle, my son will never know how his father looked and what sort of man he was,” says Nandipha. “Sons need their fathers.”

Asked what she will tell her sons about their father, Nandipha says: “Just what I know about him. He was a good man, a people’s person, someone who was very kind and loved God.”

Bonginkosi was a pastor in the Zion Christian Church who “used to love singing Christian songs. He would start singing in the house and I would follow him, and the neighbours would think there was a church going on in our shack.” Nandipha says her husband’s favourite verse was Corinthians 15:10: “But by the grace of God I am what I am: and his grace which was bestowed upon me was not in vain; but I laboured more abundantly than they all: yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me.”

For his years of labour at various mines Bonginkosi’s family will receive an R80 000 provident fund payout. Nandipha has already received R40 000, with the second half expected after August 16.

“I had to use some of that money, about R30 000, to fix this house after we moved back from Marikana and I am using the change from that to live on because otherwise all I get is the two child support grants [totalling R580 a month]. There is no money going into the bank, I am just taking money out, but how can I say ‘no, I mustn’t withdraw money’ if the children fall sick, or we need to eat?” she asks.

“I can’t buy red meat. I don’t buy sausages anymore. Or Tastic rice. I just buy the basics,” she says, longing for the time when her husband would take the family to a fastfood chicken outlet on payday. “We would get a sixpiece meal,” she remembers. “Whatever drinks we wanted – and icecream for Babalo.”

These are luxuries now. As are birthday cakes. So, when Babalo turned six earlier this year, “my child could not understand why there was no cake, but I have to spend my money on baby formula and nappies”.

She spends R120 on 50 nappies and R150 on baby formula. “But that doesn’t last to the end of the month,” she says.

Nandipha has received five food parcels from the government since August last year, but instead of mealie meal and beans, which Mihle is too young to eat, she would prefer useful items like formula.

Like many of the Marikana widows, Nandipha feels ignored and disregarded by government as she struggles to piece together her life without husband and breadwinner. “The government treats us like this because they killed our husbands, saying they were criminals. Maybe they feel we are the wives of criminals, so they treat us like dirt.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.