THABISO MOSEBETSANE

LUQHOQWENI, EASTERN CAPE

When Ntombizolile Mosebetsane asked Anele*, a friend of her husband Thabiso, to help her to look for him on the Saturday after the Marikana massacre, his first instinct was “to go to Phokeng mortuary”.

“But I wanted to do the best for my sister,” he says. So he drove around with her for hours to various hospitals and police stations — to no avail.

Ntombizolile had been desperately searching for her husband since August 16 2012. She says on that day Thabiso did not return from the mountain for lunch, as he usually did. Later that afternoon “someone told me that children are dying on the koppie” and that “police had surrounded the miners with wire and people were carrying bodies”.

“I lost all power,” says Ntombizolile. “I sat down and waited because people were returning.” But Thabiso did not. And no one knew where he was.

Later that evening, Ntombizolile “went to the mountain” but was turned away by police, who told her to go to Lonmin’s number one shaft at Middelkraal for more information.

“On Thursday night I couldn’t sleep because I didn’t know where my husband was, but I hoped for a knock on the door,” she says.

The next day Ntombizolile went to Middelkraal with the wife of another miner, but the authorities could not provide any information or lists of the dead, arrested and injured miners.

Nor did they have any luck at the Marikana police station, Wonderkop, or the Andrew Saffy Hospital at the mine.

Meanwhile, her friend’s husband called to say he was alive and “in hiding” — but that he did not know where Thabiso was.

On Saturday, Ntombizolile visited four hospitals in the area — and again failed to find Thabiso.

Her sister-in-law Motshidisi, who is an informal trader in Rustenburg, sent a text message saying she had heard Thabiso was at the Jericho police station.

Ntombizolile went there with Anele and Katiso, Thabiso’s son from a previous marriage, for an identity parade of miners. This also failed to solve the mystery.

When, on Sunday, Anele and a few others went to Phokeng mortuary and returned to say it was closed, Ntombizolile suspected “they were hiding something from me”.

On Monday, she learned it was the death of her husband.

Describing her ordeal, Ntombizolile says: “How do you have hope over five days, not knowing where your husband is?”

“August 16 reminds me of June 16,” says Anele. “It was like a dream, maybe a nightmare, this failure by government and Lonmin.”

He had been at the mountain on the morning of August 16 but left to go grocery shopping in Marikana’s squalid main strip. En route, he “saw three Lonmin buses loading lots of police into them”.

“Later, I got a call from someone who had been on the mountain to say: ‘People are dying at Wonderkop, where are you?’” says Anele, who admits to being in a state of bewilderment after the massacre, withdrawing from the world and only making contact with it again when Ntombizolile asked for his help.

In the days leading up to the massacre life in the shacklands around the Lonmin platinum mine was tense. A curfew appeared to be in place as people died to the soundtrack of helicopters roving overhead and rubber bullets being fired into the night.

Anele says: “Police were coming day and night, day and night — patrolling [the informal settlement of] Nkaneng. They were shooting at people, even if they were in the yard. I remember once we were playing a card game and they shot at us. I didn’t understand why.”

He says there is a different tension now. The rivalry between the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union and the National Union of Mineworkers continues, especially as the former was only recognised as the majority union at Lonmin on August 14 2013.

Anele, who has worked at the mine since 2008, says Lonmin has instructed miners that “no one can talk about what happened on August 16 underground. If you do they say you are influencing people and we are scared of being fired.”

He says that this directive means miners “are not free”, and that management “has put us in a pot and placed a lid over us”.

Personal differences are also simmering in the Mosebetsane family. Thabiso was described by his wife as “a man with a big heart who supported many children, even those who were not his own”.

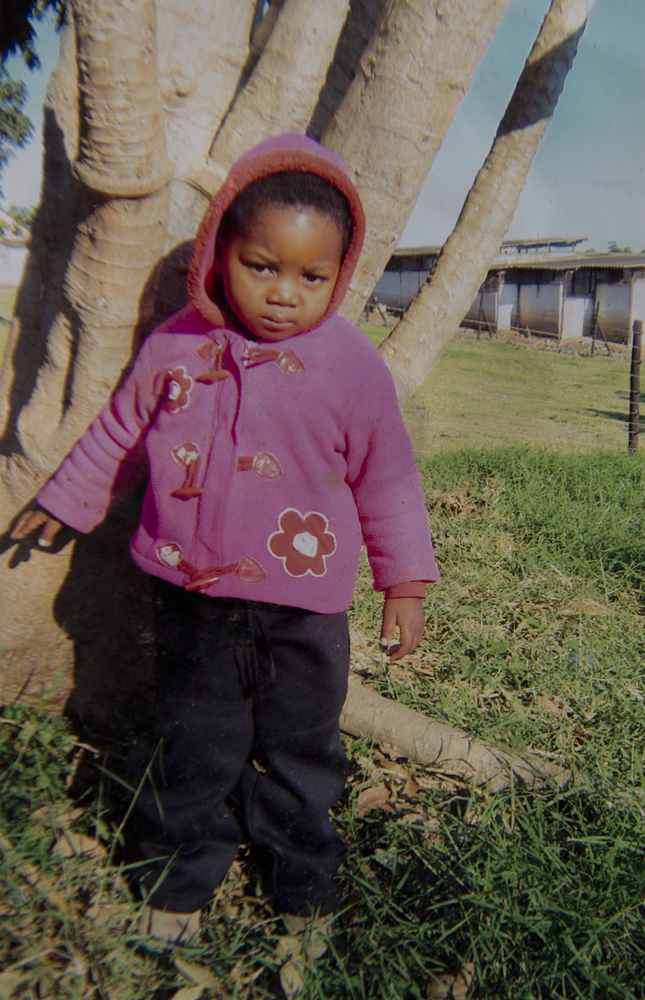

These included three biological sons with his first wife, who died in 2003, and a daughter that his second wife — who died in 2006 — brought into their marriage from a previous relationship and “who Thabiso accepted as his own”, according to his sister, Nomakhepu. There is also Chantelle, the baby he had with Ntombizolile, and the two children she brought into their marriage.

The two youngest children from Thabiso’s previous marriages live with his mother and sister near Matatiele in the Eastern Cape. Ntombizolile lives with her children in Luqhoqweni, near Lusikisiki.

Both households are impoverished and at odds over which children should be beneficiaries of Thabiso’s provident fund — and who will replace him on the mine, should Lonmin ever make the offer.

There is also no indication from government that the inconsistent food parcels handed out by the department of social development will be provided to both households — placing a further burden on the women who run them.

Looking through her handbag for her husband’s identity document, Ntombizolile comes up with some paracetamol packets: “This is what I have survived on since Marikana,” she says.

“Each and every day at the [Farlam] commission I start with a Grandpa [headache powder] and I use it again at the end of the commission. I have had a terrible headache since Marikana — that is why you see me with different painkillers.”

* Anele’s name has been changed, as he still works at Lonmin and does not want to expose himself to possible victimisation

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.