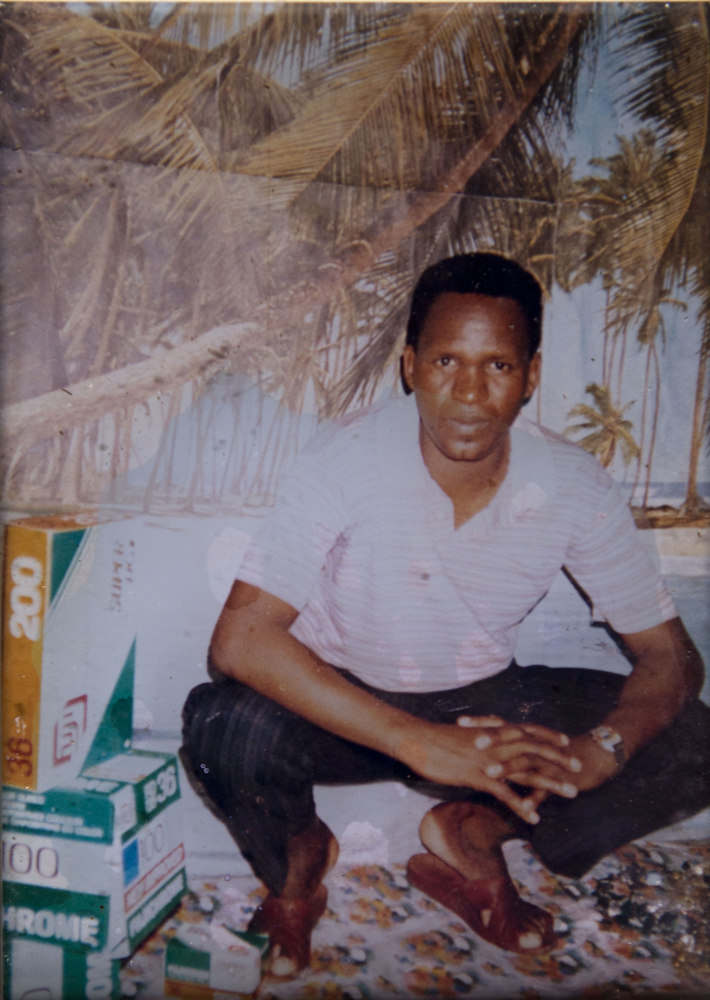

THEMBELAKHE MATI

THEMBELAKHE MATI

NTABANKULU, EASTERN CAPE

Thembelakhe Mati died on August 13 2012. His family believes they will never know who killed him, as witnesses who are still working at Marikana fear they will be snuffed out if they speak up. There is little faith in the protection the state has offered in return for their testimony.

The miner appears in footage showing police dispersing mineworkers on August 13 – fuelling speculation that they might have targeted him. But the police told the Farlam Commission of Inquiry that they found Thembelakhe’s body among the shacks around the mine and deny having been involved in his death.

His wife, Florence, believes they were responsible. “I hate all of them,” she says bitterly. “It doesn’t matter where they come from, even the ones from Ntabankulu, where I live. I hate all of them. I can’t help it.”

Thembelakhe’s uncle, Lanford Gcotyelwa, is attending the commission’s hearings. He is unequivocal in his belief that “the government must have had something to do with Marikana”.

He says the “unsatisfactory” testimony from police representatives, including national commissioner Riah Phiyegah, suggests they have something to hide.

“They had a plan and a part” in Thembelakhe’s murder, Lanford says.

“Since Jacob Zuma became president, everything we hear about the police is about shooting and killing. Zuma has shown no remorse for what happened to our loved ones,” says Lanford. “He didn’t say or do enough for what his government did.”

And now Marikana is being used against everyone else, Lanford says. During a recent march to the Ntabankulu municipal offices to protest against inadequate service delivery, he says, officials told protesters that “marches don’t help anyone because when you march another Marikana will happen”.

“But we have the right to march, to complain about the people we elected, and not die for it,” he insists.

Neither he nor Florence feels they can vote in the next election, both because of Marikana and their own circumstances: the land they live on is wild forest — idyllic to the eye; hard on the rest of the body. It has neither running water nor electricity and is far from schools and clinics. And the way is dangerous. Florence says the youngest of her six children, Siziphiwe, was killed while travelling on a school bus a few years ago.

The loss of her husband is taking a further toll. He used to send home R3 000 a month for the household. She must now survive on three child support grants, which add up to R870 a month. Her daughter Asisipho requires special sun protection cream for her albinism, which costs about R400 a month.

So their diet no longer contains fish or meat and consists of pap, potatoes or samp, supplemented by cabbage grown in the garden.

“I have a big family to feed and I get panic attacks. I feel as if I am having a heart attack and I have to sit down and be quiet,” says Florence. “Sometimes I have sleepless nights or I go to bed and I wish I never wake up in the morning.”

She says her husband would “play like a child with his children when he came home”. He didn’t like going to church, but he loved football and encouraged his son Vuyisani and daughter Yolokazi to play for the local football teams, United and New Leaders.

“He was not like other miners who had second wives at Marikana,” says Florence. “He was a quiet man who used to visit us five times a year. I could visit whenever I wanted and when I did I would find him in his room sitting quietly.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.