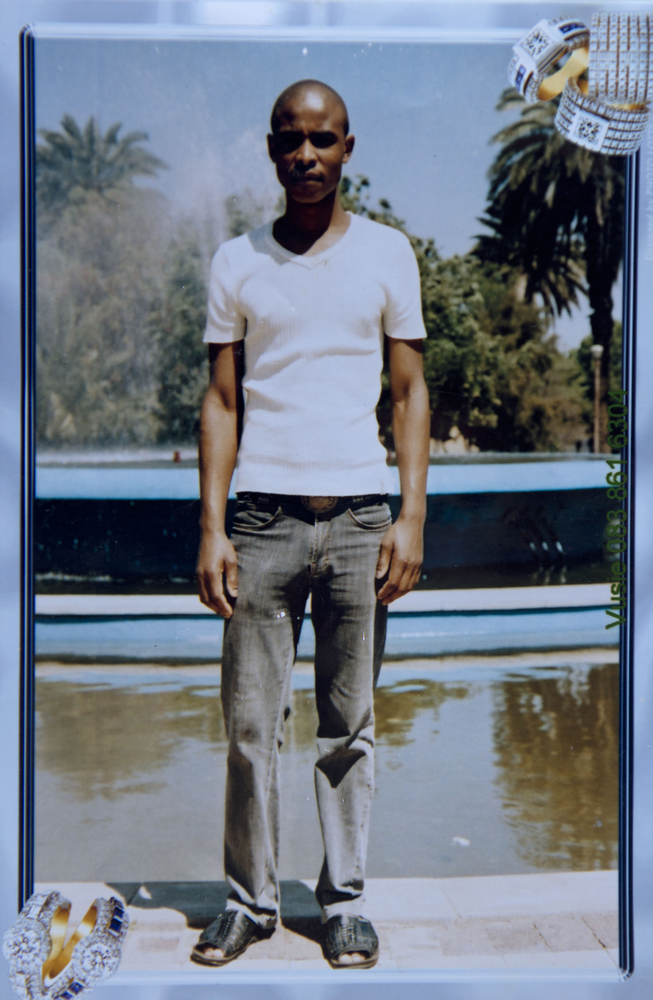

BONGANI NQONGOPHELE

ELLIOTDALE, EASTERN CAPE

Marikana’s grapes of wrath have produced a bitter vintage for the families of the dead. Trauma, unresolved grief and impoverishment converge in desperation and, sometimes, squabbles for the scant resources left behind.

The death of Bongani Nqongophele has torn his family apart, as acrimony grows over how best to use his provident fund and who to send to Lonmin in the event of the platinum mining company allowing families to replace those killed in August 2012.

Nombulelo, Bongani’s wife, is 30 years old. She wants to work at Lonmin, she says. “Because I am still young.”

She has a five-year-old daughter, Anga, who is epileptic. Nombulelo wants to ensure that Anga’s medical needs and longer term future are secure. Without the R5 000 remittance Bongani used to send home, Nombulelo is increasingly worried about that future.

But because Bongani also helped support his mother, two sisters and their 10 dependents, the elders of the Nqongophele family have other plans.

“After my son passed away we had a meeting at home,” says Bongani’s mother, Nongqondile. “The elders asked my son’s wife if we could not replace Bongani with my son Khanyile, who lives in Cape Town. My daughter-in-law just cried and cried. Now she is no longer part of the family and has moved back with her parents [near Cofimvaba].”

Nongqondile says that if Khanyile – who has a low-paying job and does not send money home to the Eastern Cape – were to replace Bongani, “the entire family would benefit”.

She says, at meetings with the other miners’ families, “it was mentioned that while the wife is named as the beneficiary [of the provident fund], there are others in the family, and the wives must play the same role as the sons … Even after the death of my son, my daughter-in-law was playing that role of buying the groceries and things [with the provident fund money], but that changed when she left the house.”

Nongqondile says that soon after the family meeting Nombulelo “packed up and left … because of that disagreement with the elders. I wasn’t here, I was in Klerksdorp.”

Nombulelo says she left because recriminations and accusations started to fly, including the charge that she had caused her husband’s death using witchcraft. She started to fear for her safety at the Nqongophele family home in Elliotdale in the Eastern Cape.

Both Nongqondile and Nombulelo say their relationship was very good while Bongani was alive.

“It pains me because I told myself I was going to stay in Elliotdale and remain with my husband’s family,”” says Nombulelo. “But I don’t feel happy that I am forced back here, to my parent’s home. I don’t think the problems with my in-laws can be fixed.”

Nongqondile also fears it may be too late for reconciliation. “I don’t know if I can see my daughter-in-law as part of the family anymore.””

The row appears set to continue for now. Later this month, the family will meet again for a traditional cleansing ceremony and the unveiling of Bongani’s tombstone. There is no telling whether anything will be resolved there.

For the 85-year-old Nongqondile, who draws a state pension while her daughters receive child support grants for their children, there are very few options left for the family. Lonmin is paying for the education of Siphosethu, a child Bongani had out of wedlock, who lives with her mother nearby, but not that of his nieces and nephews.

Nongqondile’s late husband, Mfumane, was also a miner. But he did not receive injury compensation or a provident fund payout when he was discharged.

The social development department has mooted the introduction of a sewing programme in the area, but the grand-mother worries that she won’t be able to take part. Since her son’s death, she has become increasingly frail and sickly.

“I am old,” Nongqondile says. “My husband used to beat me and abuse me, so my arms are weak. I can’t promise I can do that work.”

She says her husband was a violent man who liked order. “Things had to go his way. If it wasn’t how he liked it, he would punish everyone. Me, the family – he wasn’t picky.”

Her son often bore the brunt of his father’s physical anger, she says, and she could see her husband’s traits growing in Bongani.

“Whenever things were not going his way, he had a short temper and would also start beating up people … Bongani liked drinking and he always started fights with the other boys, but his father didn’t entertain his drinking and fighting.”

These characteristics, says Nongqondile, made her worry about Bongani’s safety during the strike.

Nombulelo remembers a “charming” man who liked the pop group Westlife and started wooing her even before they met. Bongani had first set eyes on Nombulelo in her sister Nosipho’s photo album – they were neighbours in Klerksdorp, where he worked before moving to Lonmin in 2011.

“After he saw the picture he started calling me all the time,” says Nombulelo. “At first, when he started contacting me he used to say ‘I love you!’ I told him, ‘Hey, we have not met, how can you love me? Let’s wait until we meet in Klerksdorp.’”

They met in 2007 after Nombulelo went to Klerksdorp to look for a job.

“I usually don’t trust people very easily, but I felt I could trust him,” she says. “Everything just attracted me to him: the way he talked and the way he charmed me, I knew he was a good man.”

They were married a year later and, after Anga was born, the couple started building a new house near the Nqongophele family homestead.

Domestic life seemed blissful. In a lighter moment, Nombulelo remembers that Bongani’s favourite meal was rice, meat and vegetables – always with white bread: “I used to warn him that white shop bread would give him piles, but he loved it.”

Marikana changed all that.

Nombulelo remembers bathing at the Nqongophele family home on the Saturday after the massacre, and hearing “angry voices” outside. Bongani, who usually called twice a day, had not been reachable since the morning of that Thursday.

She says she tried to kill herself when the news of Bongani’s death filtered through.

“I knew he was gone. I took the cow dip medication and I drank it. I knew it marked the end of my husband, so I wanted to mark my own end, too.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.