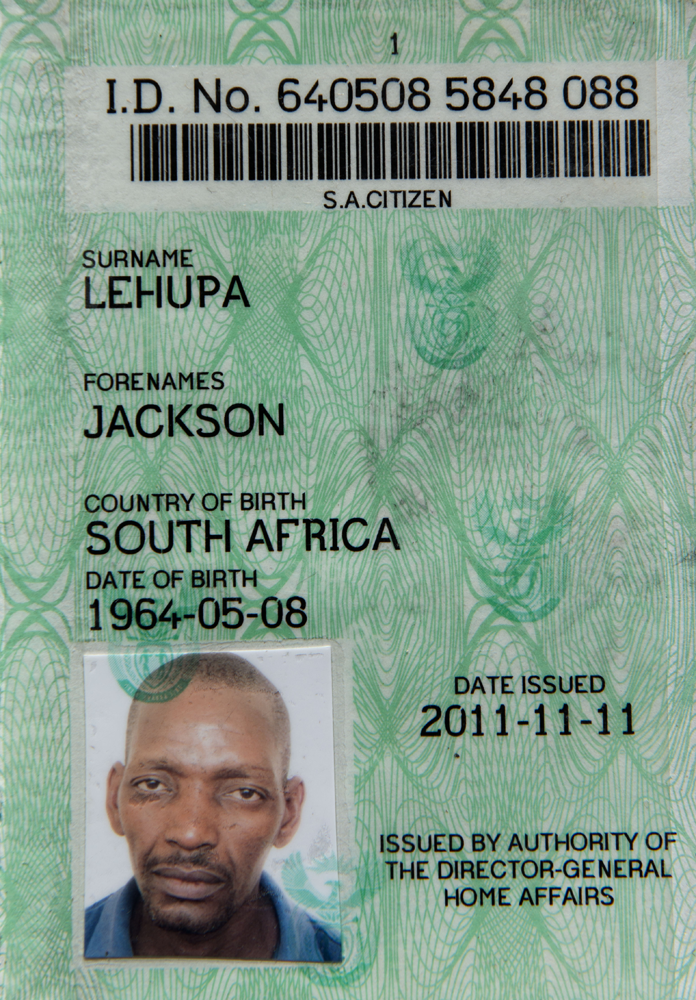

JACKSON LEHUPA

MATATIELE, EASTERN CAPE

Culture and poverty connive in the aftermath of the Marikana massacre. For Malukisang Lehupa it means marking the end of the mourning period for her husband, Jackson with a “semi-umembulo” — a cleansing ceremony.

“We can’t afford to slaughter a cow now,” says Malukisang, “So we are doing half the ceremony now and slaughtering a sheep. Maybe in a few months when I can afford a cow we will do the ceremony properly.”

Malukisang burns the mourning clothes she has worn since her husband’s death after going through the shave-and-slaughter routine of the umembulo — her head is shaved clean while the sheep’s throat is slit and it is skinned.

But there are marked differences from a full ceremony. There is no bathing with the bile from the gall bladder of the sheep: that will be reserved for when the family can afford a cow. The gathering is also much smaller than the usual large communal commemoration: sheep feed fewer people than cows. A full ceremony, says Malukisang, can cost between R20000 and R30000.

Malukisang says she was determined to do the partial ceremony in an attempt to move on from the death of her husband. “[But] I still feel the pain, even though I took off the mourning clothes. In my heart, the pain still feels new”.

Sitting in the mild May sunlight, outside her rural home between Matatiele and Mount Fletcher in the Eastern Cape, a few nicks appear on Malukisang’s increasingly bald head.

Her neighbour, Malebohang Motsokotsi, who is shaving, mutters in her defence that “if the razor was sharp, this would be done a long time ago — [the problem is] these Chinese fong kongs [cheap goods]”.

The yard bears testimony to Jackson’s death. A new three-room house is close to completion. “It was only three lines of bricks from the foundation when he died,” says Malukisang. She has used the money from Jackson’s provident fund to complete it.

Malukisang’s son, Sthembiso (18), still feels the loss of Jackson in an acutely masculine way. “I miss my father a lot,”he says. “When I think of the things he promised to do for me, it’s painful. “Last year he promised he would take me to the mountains [for circumcision] in December, but he died. My mother said I would go this year in December. It is important that I go to become a man, but it is expensive.”

A traditional Xhosa blanket, he says, costs about R500 and one needs to go to initiation school with a suitcase of new clothes.

Malukisang bemoans the fact that she cannot even afford winter clothes for her children. The lack of money since Jackson’s death has aggravated Malukisang’s emotional distress. Without the R2000 he sent home every month, she must rely on the child support grants received for four of her six children.

The burden has been slightly alleviated by three of her children attending boarding school in Johannesburg, which Lonmin pays for. But she did not have the proper school and identity documents available at the beginning of this year so both Sthembiso, who is in grade eight, and Sizwe (14) have remained with her and will only register at a boarding school next year.

Sending children to boarding school has helped Marikana families to cope with the financial vacuum created by their husbands’ deaths — and ensured their children get a solid education while being properly fed and clothed. But Malukisang still breaks down and cries uncontrollably when talking about the struggle to safeguard her children’s future.

“What is really painful is that the police who killed my husband, they are still working and their children are eating every day,” she says. “But my children are going hungry and the government does nothing and the mine does nothing.”

“The thing that is stressing me more and more is that the people who are standing by the widows are being killed. Steve [Khululekile, an organiser from the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, or Amcu] was killed in May and now I am worried about [Amcu president Joseph] Mathunjwa,” says Malukisang. “He supports us, he is a father to us, and I am worried that he will be next.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.