On August 16 2012, 34 people, mostly employed by Lonmin platinum mines, were killed after police opened fire on striking miners.

The strike, which had begun on August 9 over a wage dispute, was marred by intimidation and violence. Ten people, including two policemen and two security guards had been killed.

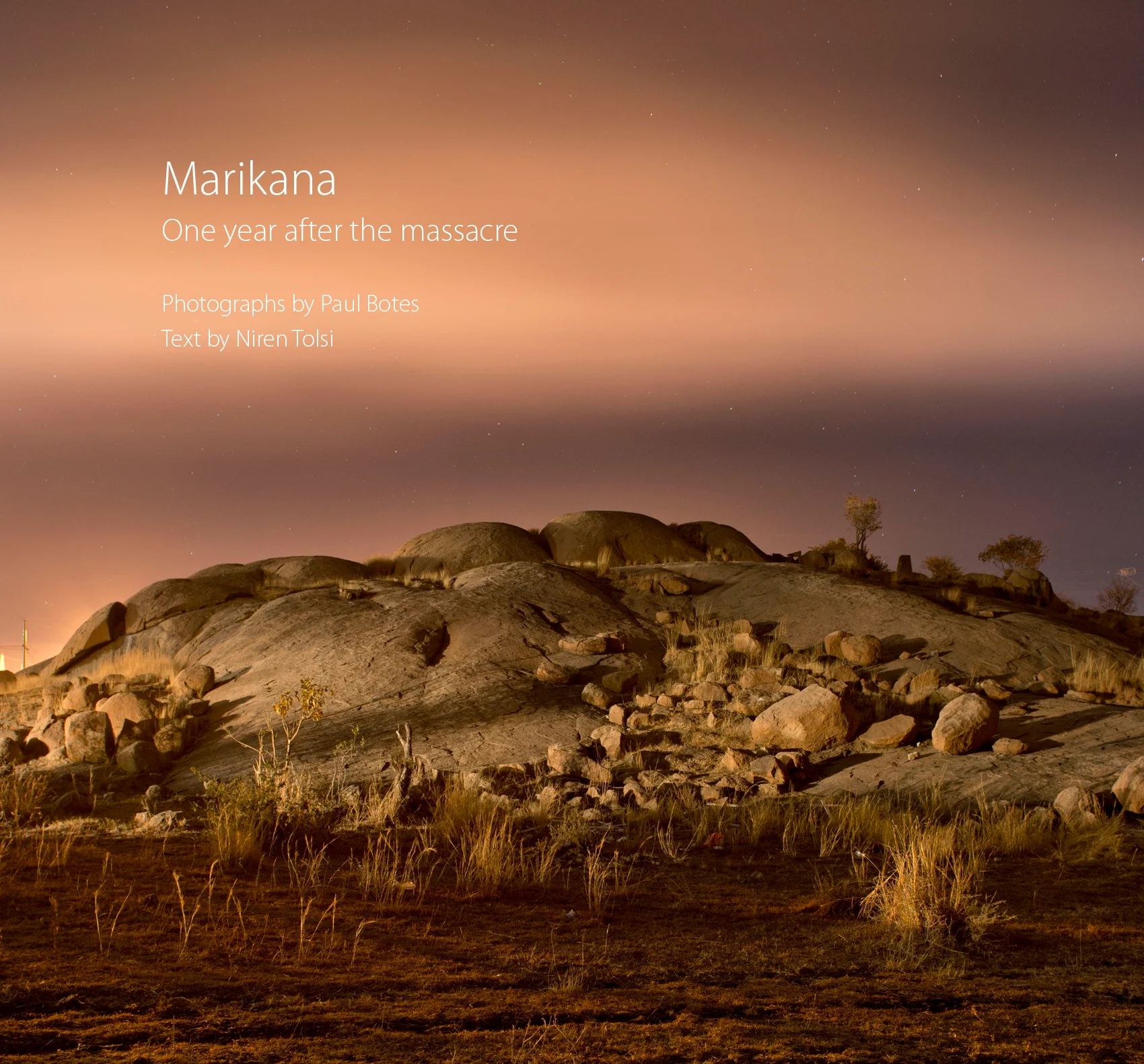

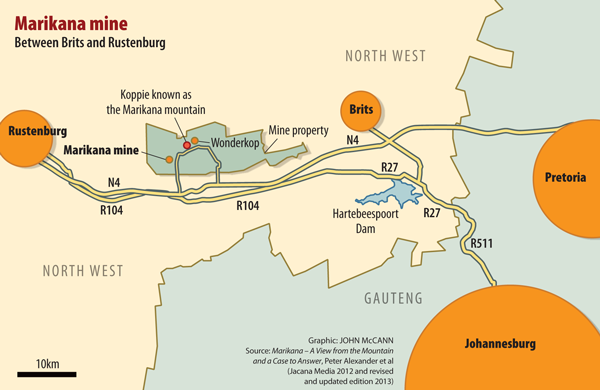

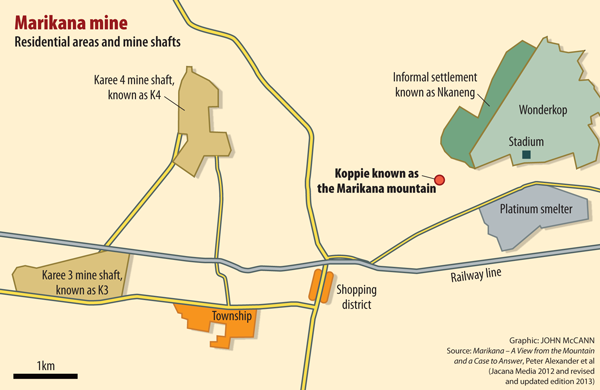

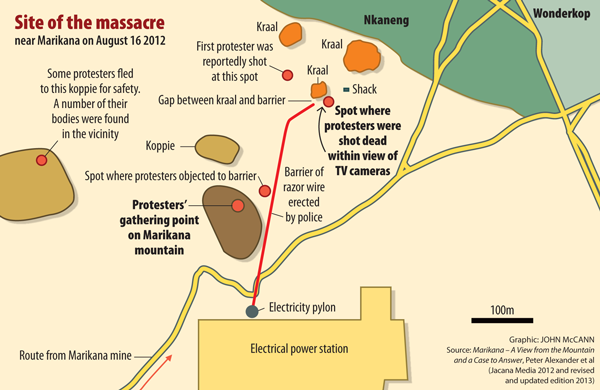

A koppie, near the Nkaneng informal settlement, had become a gathering place for striking miners. On August 16 thousands of miners who had gathered at the koppie were ordered by the police to disperse, when they did not the police opened fire on them with automatic weapons, killing 34 and injuring scores of others.

This special report examines the consequences of the killings through the eyes and voices of those most affected: the families of the dead miners.

The project was initially conceived when Mail & Guardian pictures editor Paul Botes attended the funeral of Molefi Ntsoele in the remote village of Diputaneng in the Lesotho mountains in September last year. It took shape after Botes discussed his idea of a wide-ranging focus on the families of the dead miners with senior writer Niren Tolsi

The lack of interest shown by the government officials tasked with attending to the dead miners’ families highlighted the vulnerability of these people and their communities. It became important to understand the consequences of the Marikana killings on families and communities that were already marginalised and impoverished.

Return to Marikana

What happened during the fatal miners’ strike in Marikana in August 2012 did not end there. Thirty-four people were killed in the massacre on August 16. Those miners who survived and were arrested say they were tortured and brutalised by the police. People also died, violently, before and after that date.

Families were left without husbands, brothers, sons and fathers. And a daughter and mother: Pauline Masuhlo was an ANC councillor in the Madibeng municipality and a campaigner for better social conditions in the squalid informal settlements around Lonmin’s shafts. She died from injuries visited upon her during a government clampdown of Nkaneng informal settlement on September 15.

The nuclear and extended families in rural areas – and sometimes satellite “second” families at Marikana – were shattered by the violent manner in which their loved ones died, and are still struggling to deal with the trauma. But they are also struggling in a material sense, deprived of their breadwinner’s wages and remittances, so important for survival.

Marikana family liaison for SERI, Khuselwa Dyantyi, discusses the effect Marikana has had on the miners’ communities.

Rural communities have lost people who put aside portions of their wages to buy football kits and balls for the local teams they grew up in and coached. They have lost mediators, drinking companions, and elders who advised on issues affecting them. Churches have lost pastors and choir members. Shebeens have lost scallywags.

Marikana has changed families and communities across South Africa. It has certainly changed how they see their relationship with their democratically elected government.

This supplement is the first step in a project that started in December last year and will continue for another year at the very least. It seeks to answer the question: What happens after Marikana?

These are complex answers that cannot be fully documented by two journalists, but the project does seek to move away from the mainstream media’s snapshot pictures and easy headlines. It aims to investigate the real cost of Marikana to families, to communities and – through this microscope of the intimate – this strange new South Africa that Marikana has ushered in.

To do this requires being embedded in space and subject. It requires returning the journalistic form to its best traditions of immersion and social investigation. It requires time, or “slow journalism”. It requires returning.

Santu Mofokeng’s vital documentation of sharecropper Kas Maine was not an Insta(nt)gram exercise. The work of social documentary photographer Chris Ledochowski in the Cape Flats emerged from him “becoming” a part of those communities.

Niren Tolsi on seeking answers beyond the political.

These are singular individuals with different training, drives, demons and curiosities. But their art of composition, light, drawing out texture, depth and attention to detail was honed in some way by the social documentary approach to go back, to return.

In doing so these characteristics of photography transmuted onto the national narrative and how South Africa understood itself. Their work shed light, added depth to knowledge, texture to understanding and brought out the detail in this country through the little-big stories they told so artfully.

Neither Paul Botes nor I consider ourselves in the league of Mofokeng, Ledochowski or the many fine writers and photographers who have documented this contradictory and sometimes cruel country with such bravery and intelligence.

But, with this project, we do subscribe to a belief that journalism should be thoughtful, responsive, empathetic and relevant.

Niren Tolsi explains the ‘slow journalism’ approach to the project.

We feel this is important in an age when journalism can be reduced to superficial, instant news. We feel it is important because we, South Africans, need to understand what happens after Marikana: to the families, and what is happening to ourselves and to our democracy.

This is vitally important. In the eight months we have spent with them, we have seen take deep root in the Marikana families the overwhelming sense that they have been abandoned. By government, by Lonmin and by their fellow South Africans.

There is scant political will to provide the financial and structural mechanisms required to ensure that a stuttering Farlam Commission of Inquiry delivers quickly on its mandate to uncover the truth of the fatal strike and give closure to the families.

With both a civil action suit by the families’ lawyers, supported by the Socio-Economic Rights Institute, and Lonmin’s offer to allow family members of the slain miners to replace them on hold until the Farlam Commission’s findings have been concluded, lives remain in flux.

Traumatised families dealing with unresolved grief are descending further into poverty.

Our world can never be the same. What happened at Marikana was a deep echo from our apartheid past. It was unrestrained and brutal. It was also state-administered.

The attendant imagery of Marikana is frighteningly cyclical: the massacre recalls all too fiercely the killing of students by apartheid police on June 16 1976 in Soweto and the Sharpeville massacre of March 21 1960 when 69 people died.

It especially echoes the Bhisho massacre of September 7 1992 when the Ciskei Defence Force killed 28 ANC supporters who were demanding free political activity in the former homeland, and, in the confusion, one of their own.

There was razor wire rolled out at Bhisho, too. Armoured vehicles and helicopters were present. And there was an attempt to escape through security force lines that was led by Ronnie Kasrils.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission noted: “When the shooting started there was complete chaos. None of the deponents reported any warning from the soldiers before the shooting started. Most did not know where the shots were coming from; many were convinced they were being shot at from the helicopters.”

The miners congregating on the Marikana koppies is also reminiscent of the Pondo Revolt of 1960 and their gatherings and massacre on Ngquza Hill in the Eastern Cape, a province where the majority of the dead miners came from.

So too is the sight of the helicopters that hovered over the miners and the massacre last year.

Jonny Steinberg, in his paper, “A Bag of Soil, A Bullet from Up High” – included in the book Rural Resistance in South Africa, documents a source’s retelling of the massacre at Ngquza as passed on by a previous generation: “The whites took Botha Sigcau, king of Eastern Mpondoland, up in a helicopter. They flew him to Ngquza, and there the helicopter stopped, hovering just over the rebels. Then the white commander put a rifle in Botha Sigcau’s hands, and he said: ‘Whether we end this rebellion is your decision to make. We can do nothing if you cannot fire the first shot. The choice is in your hands, not ours’. Botha Sigcau thought for a little while, took the rifle from the white man, aimed at the rebels below, and fired the first shot. It hit a man in the chest and killed him. That is how the massacre began.”

South Africans have seen the footage of the Marikana massacre. The country knows who fired the shots. What we as a nation are still hoping to answer, are the more political and philosophical questions of who took the gun from the metaphorical “white man” and why the first shot was fired.

These are questions this project hopes to answer with the voices of the families of those who died in Marikana.

It is a mammoth project. It involves driving long distances into the deep recesses of rural South Africa – and getting lost, often. It has meant navigating the roles of traditionalism and patriarchy involved in a community deciding who gets to tell what stories, and in how grief is confronted. It has meant encountering the indomitable spirit of South African women often.

We hope to do their stories justice.